“Man, I can’t believe how cloudy the water is,” Gator apologized for the 50th time over the last three days.

We were wading the flats of Matagorda Bay near Port O’Connor on the South Texas Gulf Coast on the last morning of a long October weekend. While the skies were blue and the company wonderful, sight casting with flies was tough.

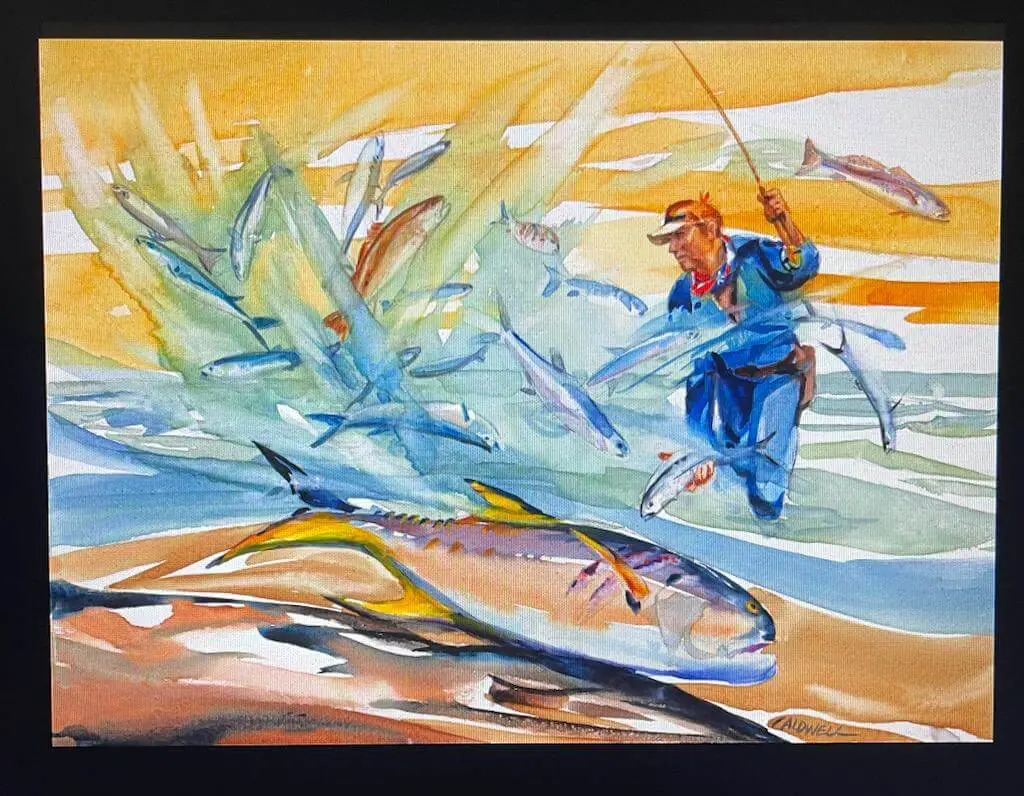

I was fly fishing for big autumn bull redfish with local guide/master chef Gator Garcia, host Bob Haley, Texas wildlife artist Sam Caldwell, and Texas conservationist Chris Smisek. Southeast Texas had experienced a soggy September as evidenced by full streams along the way to Port O’Connor from Corpus Christi. My friends described our predicament this way: “Fresh water pours into the bay at a faster rate than it flushes out. Changes temperature, salinity and clarity. So, if you’re a redfish, you go where you’re comfortable, which is usually deeper water.”

Which is not what this Colorado fly angler wanted to hear. We had a mixed group of spin and fly fishermen and Gator, a Corpus Christi spin angler his entire life, was doing well casting plastics, broad and deep. While blind casting Clousers might get you some ladyfish, grunts, small reds and speckled trout, it is also a sure recipe for an aching shoulder. On this last morning, Gator and I walked the shoreline, peering into grass beds and sandbars for shadows, wakes, tails, anything that looked fishy.

“You gotta push some water and make noise today, man.” Gator fished through my fly box, ignoring dozens of Clousers of all sizes and colors that I had been tying for weeks in anticipation of the clear Matagorda flats.

“What’s this–have you been sandbagging flies on me?” He held up a mullet-sized streamer that I had dubbed the Matagorda Pandelarium in honor of Sam Caldwell. Sam, as a lifelong Texan, always seemed to have the right word and metaphor handy while fishing. And if he didn’t, he’d just make one up…

I reluctantly tied on the Pandelarium. Under the right conditions, it’s a joy to fish, right conditions being a 9-weight fly rod, light wind and sight casting to fish on the prowl. This morning, I was blind casting into a 10-knot headwind with an 8-weight rig, about as pleasant as casting a waterlogged sweat sock. Gator punched me and pointed. “There’s a nice slick forming at the head of that sandbar. Put that ugly thing at 9 o’clock, about 40 feet.”

I delivered the waterlogged Pandelarium flawlessly at 1 o’clock and 10 feet. Gator shook his head, muttered something in Spanglish and resumed casting plastics.

When I am catching nothing, I do make an attempt to at least look good doing it. I turned away from Gator, returned the Pandelarium to the fly box and tied on a chartreuse Clouser. A few double haul casts and the Clouser plunked down at 9 o’clock and 40 feet. Wham. My rod arced as a fish tore across the sandbar, cutting a foot-high rooster tail of water.

Gator smirked. “Amazing what happens when you follow directions. Oh look, you got

another ladyfish.”

“Yeah, I can see that, Gator.”

“We call that a poor man’s tarpon.”

“Yeah, you have shared that with me a few times this weekend.”

Another thing shared with me this weekend was the power of “Ladyfish grease,” by Gator’s brother Rene. When fish are less than cooperative in these parts, a little ladyfish grease can lubricate the rustiest redfish jaw hinges. I confess that I held the ladyfish a few seconds longer than necessary to remove the fly. And then I held the Clouser a few seconds longer than needed with the same fingers that had held the oily ladyfish.

So, sue me for a sweetened fly. Double haul, 9 o’clock, 40 feet. WHAM. Note CAPS. This fish ran deep and strong off the sandbar into some weed beds. I could feel its shoulders as the 8-weight couldn’t turn the fish back towards me. I adjusted the drag and took what the fish gave me. A gorgeous purplish-nickel-silver speckled trout was soon splashing at my waist. While the most beautiful fish in the world is a male Colorado River cutthroat in spawn dress, a Texas speckled trout is right up there in the top five. I popped the fly from her jaw and the fish disappeared.

As Gator and I waded along the drop-off of a knee-deep sand peninsula, a golf cart pulled up on the island beach. Bob and Sam propped up their feet on the dash and sipped coffee as if waiting for the foursome ahead to play through. The island that we were fishing is part of a series of islands where the locals drive four big posts into the sand, build an elevated sleeping area about 10-12 feet off the ground and construct world class tequila bars at ground level. The bars are accessed by boats and golf carts and are sanitized every five years or so by Texas-sized hurricanes.

As we waded along a shallow reach, the wind died down and water clarity improved. Gator and I stopped casting and scanned the sandbar, noticing nervous mullet near the drop off about two o’clock at 40 feet. I looked at Gator. He looked at me. We both studied the nervous water. All we needed was music from the three-way showdown of “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.” To break the tension, I fired another shot at nine o’clock and 40 feet. Wham. Note all small letters. A 12-inch lady fish.

“Dude,” Gator yelled, “reel that fish in NOW and drop one in front of that nervous

water! Those mullet are REALLY nervous.”

The hooked ladyfish was leaping, struggling, splashing and, from what I could see, bleeding. I’m no Texas gulf coast fishing guide, but that seemed to be a harmonic convergence of wrong place/wrong time/wrong behavior in the Texas Coast Ladyfish Survival Guide. The fish darted across the sandbar and jumped into the previously mentioned nervous water.

The water exploded.

Several dozen mullet went Defcon Level-4 berserk. Frantic baitfish flew three feet airborne headfirst, tail first and cattywampous as a steel-blue back topped with a 20-inch yellow sickle dorsal fin rocketed from the green depths onto the sandbar. The jack crevalle had the size, color and temperament of an industrial trashcan lid. It tore through the mullet on the sandbar and appeared to be locked in on the struggling ladyfish on the end of my line.

“Get the ladyfish off,” Gator yelled, “and throw something at that jack!”

I frantically stripped in line, creating a spaghetti pile of flyline around my feet while a cloud of mullet stormed my way. The hooked ladyfish led the pack, water-skiing to me at warp speed, followed by airborne mullet while the jack, halfway out of the water was closing in at the rear.

I grabbed the ladyfish and attempted to remove the hook with my pathetic Colorado brook trout hemostats as the mullet mess crashed through me, slamming into my shoulders, face and then into the water behind me. Bent over and fumbling with the ladyfish, I looked at the jack, who had turned broadside about 20-feet away from me, moving toward shore. His side was scarred, and his eye was above the water’s surface. I detected a glance of contempt.

The jack circled back toward the open water. The eye facing me now appeared glazed

over and his flank was scarred. This fish had been in a scrap or two. He casually made

his way off the sandbar and disappeared into the depths.

Gator was bent over laughing. “Dude, that was awesome. You were screaming like my

eight year old niece!”

Gator’s fishing and culinary skills are matched only by his gift of humiliating angling

colleagues.

I removed the ladyfish, who was now comatose from shock, and pitched her toward a few bored pelicans behind me who had a “you want that fish?” expression. I reeled in fly line, spitting out mullet schmutz, wiping mullet scales off my arms and shoulders with as much dignity as I could muster.

We splashed toward the golf cart where Bob and Sam’s feet were still propped up on

the cart dashboard, coffee mugs in hand. Gator was about ten feet in front of me, his

shoulder shaking from not-so-suppressed muffled laughter.

I slogged up to the cart and looked over at Bob.

“You saw that, right?”

Bob (stoically): “Saw what?”

I glanced over at Sam, looking for any kind of comfort and confirmation.

Sam grinned. “Now, THAT was pandelarium.”