Last updated on January 6th, 2023.

In a few rivers of the Balkans swims a fish that only remotely resembles a brown or rainbow trout – the mysterious softmouth trout. Hans van Klinken explores the rare species.

Softmouth Trout: How it all Started

A few years ago the Continental Trout Conservation Fund (CTCF) organized the first International Trout Masterclass in Tolmin, Slovenia. Gašper Jesenšek, owner of Soča fly fly-fishing shop and member of Continental Trout Slovenia, was responsible for the outstanding organisation during the event. René Beaumont, founder and president of this rather young organisation, did an amazing job of bringing together a cadre of senior experts from different countries, continents and cultures.

Zeb Hogan (USA), Asghar Abdoli (Iran) Shaun Leonard (UK), Aleš Snoj (Slovenia), Össur Skarphéðinsson (Iceland), and Dušan Jesenšek (Slovenia) are only a few names from a long list of participants. The goal of the event was to introduce young, enthusiastic students to what conservation is really about. At the same time, to also mould them into mature future leaders. With the intention of helping them establish a solid network among our next generation of conservationists.

A Scientific Outsider

Being a complete outsider to the scientific world of conservation, René and his team set up an impressive and valuable “blue print”. It enables young conservationists to organize similar events in their own countries. There was an excellent mix of professional lectures, workshops and classes. The team exchanged their visions, discussed worldwide environmental problems. They offered ideas and solutions for all attendees. The event did not just open my eyes to conservation issues. It also gave me a completely new understanding of how so many unknown and amazing people are fighting hard. They fight environmental problems, the effects of global warming, and overpopulation.

I gave a presentation on my views on fish, rivers, nature, wildlife and even environmental problems, based on my 45 years of fly-fishing experience. I had adapted my lecture particularly for this event. Many of the participants had never fly-fished. On the last day of the Masterclass, each of the young students explained which conservation work they were involved in. Some of these lectures made such an impression on me that I have since delved far deeper into matters of conservation.

Making new Friends

During the event I made a lot of new friends. One of them being Ado Adnan Zvonić from Bosnia. Ado wrote me an email a few months after the Masterclass. He desperately sought my help. It seems he was planning to organise a small fly-fishing and conservation event in 2015. It was meant for the kids in his area in southern Bosnia. I had told him that I do lots of fly tying and fly-fishing classes with kids. That’s why I couldn’t refuse his request. Especially when he had invited me to help with such great enthusiasm.

I offered to do a workshop for the kids. I supplied all the materials, as long as he arranged a good location. Knowing it would be impossible for him to find enough materials, he jumped at my offer. In return, he asked if it would be possible for me to stay a few days longer. He wanted to show me the River Neretva and its surroundings. Maybe we could fit in a little fly fishing as well. Now it was my turn to jump at the chance. It was a unique opportunity to fish the river he had mentioned in his presentation in Tolmin.

I was completely in awe of his presentation. In particular when he started to talk about the very rare softmouth trout (Salmo obtusirostris). They are only found in the River Neretva and a few other river systems in the Balkans. I had been under a sort of softmouth trout spell ever since I saw some amazing photos of them a few years ago. I knew right away that this fish was something special. That it would have to be handled with extra care if it was to survive. Having fished the river and having caught a few softmouth trout, the spell has just grown!

Looking into the Softmouth’s DNA

Since the Masterclass, I read a lot about species such as marble and softmouth trout. The softmouth trout stirs huge interest in me because of its rareness. It is easy to understand why there is so little knowledge about this wonderful species. I did my research on the web and in the occasional scientific studies and reports that exist. Soon I became confused by all the different names, (local names and scientific names) that I encountered. The scientific name went through many taxonomic changes over time. This makes things even more complicated. Especially for someone like me without any biological or scientific background.

Luckily, recent comparative morphological studies and analyses place the soft mouth trout as close to, or even within, the genus Salmo. Aleš told me about mitochondrial and nuclear DNA analysis. Softmouth trout exhibit a closer relationship to the brown trout (Salmo trutta) than Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). This finding refutes the classification that recognizes the soft mouth trout as a separate genus Salmothymus. It recommends its reclassification on the species level as Salmo obtusirostris. (Have a look at the web site of the Balkan Trout Restoration Group and visit their research pages).

In this story, I want to give the softmouth trout some extra, but not too scientific, attention. Not many people know about the existence of this beautiful fish. Many see the species as a misshapen trout, or a cross between a brown trout and a grayling. Sadly, the softmouth trout is often killed due to ignorance. The killing or removal of softmouth is strictly illegal though. The fish is critically endangered due to damming, hybridization, poaching. The impact of natural and anthropogenic pressures can be felt as well. This is why they are highly protected in the last few rivers they inhabit. They are on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species!

The Characteristics of the Softmouth Trout

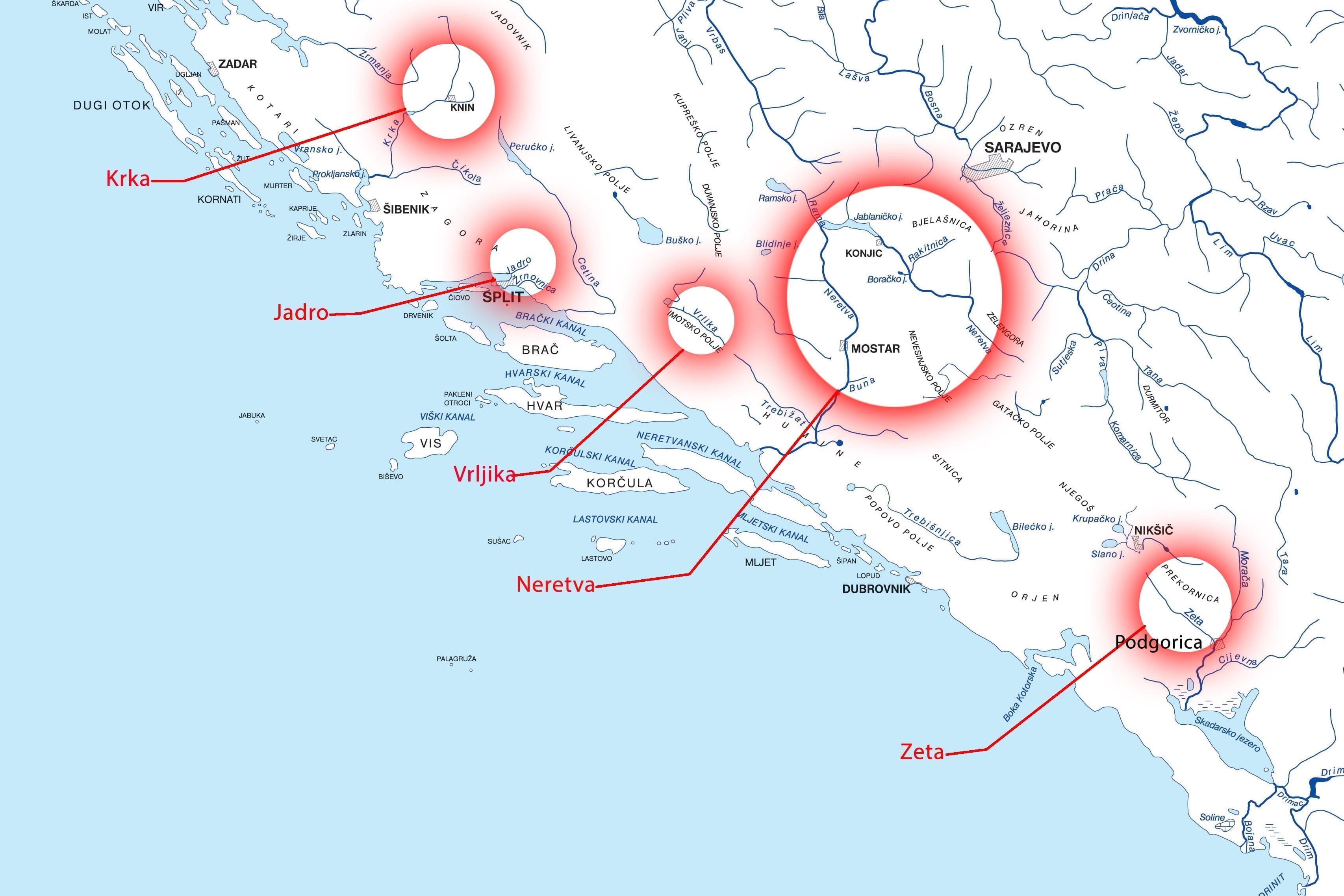

Softmouth trout only exist in rivers of the western Balkans that drain into the Adriatic Sea. Heckel was the first to describe this species from three localities. The rivers Zrmanja, Jadro and Vrljika as Salar obtusirostris in 1851. Later on, the fish was found also in the Krka River in Dalmatia, in the Neretva river system and in the Zeta River in Montenegro. The description of softmouth trout in the Zrmanja River is intriguing. After this description softmouth trout have never been found in the Zrmanja river ever. It is assumed that the specimens that Heckel studied actually came from the neighbouring Krka river.

Generally speaking, some characteristics of softmouth trout are very similar to grayling. Their external appearance, but also some of their reproductive behaviour. They spawn in spring as grayling do, while brown trout spawn in winter. Similar to grayling, but contrary to brown trout who cover the eggs immediately after spawning, softmouth trout do not cover their eggs immediately (for details in spawning behaviour of softmouth trout see an interesting article by Esteve et al., 2014).

Similarities with the Grayling

Again similar to grayling, softmouth trout feed on fauna found in the bottom sediments of rivers and lakes, being so called benthos feeders, and show generally grayling-like feeding behaviour. They usually hold in the deep pools in rivers, not near the banks like brown trout often do.

Softmouth trout exclusively populate rivers where grayling were never present, or were never native, for example the Neretva River, where grayling are an introduced species. However, grayling and softmouth trout are not able to hybridize, which is a proof of their distant relationship. So it seems that softmouth trout evolved some grayling-like characteristics because they required these characteristics to survive in a grayling-free niche.

A pre-glacial origin for softmouth trout

The fact that the softmouth trout is a spring spawner suggests it may have evolved before the Pleistocene epoch. This means that softmouth trout require warmer water for spawning compared to glacial species, such as brown and marble trout that require colder water and thus spawn in winter.

This is a consequence of evolution, that relates to softmouth trout originally spawning in warmer water temperatures. And it makes sense in the case of softmouth trout, because the distribution range of this species was never covered by ice, or directly influenced by any ice age. So softmouth trout have never been required to adapt to colder water. Thus it appears that softmouth trout evolved in the very same places they occur in today, while other Salmo trutta-like trout species now found in the Balkans, colonized these same places far later.

When looking at morphological characteristics, softmouth trout are generally easy to recognize by their elongated snout and small, fleshy mouth. There is some similarity to the sharp-snouted lenok salmonid species (Brachymystax lenok) found in central and eastern Russia, and also widely in northern Mongolia. They are not, however, related, and probably developed these characteristics independently through parallel evolutionary forces.

Softmouth trout also have rather large scales, and quite a large body depth. Some populations of softmouth trout have developed specific morphological characteristics depending on the particular river system they originated in. This is why scientist put them into four generally considered subspecies, while the Vrljika softmouth has no subspecies name. So let’s have a look at the rivers they inhabit.

The Krka River (Croatia)

Typical for the softmouth trout from the Krka River (Salmo obtusirostris krkensis) is their blunt snout, which gives them a distinctly peculiar look, and is why locals call them “evil mouth trout”. Amazingly, this species’ mouth is a similar to the blunt-snouted lenok also found in Mongolia. In my modest opinion, this subspecies of softmouth trout must be one of most endangered fish populations in the world because not only are they highly poached but also inhabit a very restricted part of the river, no longer than a few hundred metres.

When an electrofishing sampling campaign was performed in the Krka River twelve years ago, the softmouth trout were still there. It was nice to observe large specimens, swimming around in the deep pool beneath the bridge. Nevertheless, only brown trout were caught but no softmouth; the chased individuals successfully avoided the electric field and furiously withdrew from the “danger zone” into distance while moving into the deep pools of the river. Another grayling similarity! So, the breeding material for the Krka softmouth trout restauration was available at that time.

However recommendations by conservationists to spread the adults of this unique population into similar streams flowing in the Adriatic Sea were not accepted, and it is probably now too late to do so. Artificial propagation of the softmouth trout in hatchery has recently been successfully established by Croatian scientists for the Vrljika softmouth trout. It is about time now to undertake the same conservation action for the Krka softmouth trout as well and use the artificially produced offspring to create new populations. Otherwise the extinction of the Krka softmouth trout seems just a matter of time.

The Jadro River (Croatia)

This softmouth trout (Salmo obtusirostris salonitana) is confined to the River Jadro, a very short river (about four kilometres long) emptying into the Adriatic Sea near the town of Split. The subspecies named “salonitana” (or “solinka” as the locals call it) is named after the historic Roman town of Salona, today Solin, which is situated at the mouth of the River Jadro. Sadly, the lower and middle parts of the Jadro River have been destroyed by pollution from a cement factory, but the upper parts still hold a dense population of softmouth trout. In their external appearance, Jadro softmouth trout are more like brown trout than any other softmouth trout population and they also show some striking similarities to the Adriatic brown trout. Their behaviour is also unusual.

For example, they prefer to rest on the ground between stones or water plants as brown trout often do. Interestingly, molecular studies showed that the Jadro softmouth has brown trout mitochondrial DNA, but the nuclear DNA of softmouth trout. Taking all these facts into account, salonitana is likely to be a hybrid entity that evolved from ancient natural hybridization between the brown and the softmouth trout a long time ago. This is an important example of the complex evolutionary pathways that often seem to be involved in the processes of trout diversification and speciation.

In 1965, 24 adult Jadro softmouth trout were translocated to the adjacent, fishless, Žrnovnica River, which is ecologically very similar to the Jadro River. The new population has adapted well to its new environment and now represents a valuable back-up gene pool for the highly endangered Jadro population.

The Vrljika River (a.k.a. Vrlika) (Croatia-Bosnia Herzegovina)

This soft mouth trout is the only salmonid populating the River Vrljika, which connects with the Neretva system via underground passages. The Vrljika population have been least studied and it hasn’t even gotten a subspecies name. Moreover, it was declared extinct by Mrakovčić and Mišetić in 1991. However, in 2004, when Aleš Snoj and his team were doing some fieldwork on the way back from Montenegro, they discovered several soft mouth trout and were able to obtain samples for DNA analysis. The softmouth trout was back, and it seems that a completely overlooked population had been rediscovered.

Sadly, they also found fish traps, so poaching is another serious problem here as well. The Vrljika softmouth is closely related to the Neretva population because of this unique underground connection with the Neretva River system. According to molecular data obtained by Aleš, he was able to tell me that the Vrljika softmouth is the only one out of the five known species that seems to be completely genetically pure. They are also the only softmouth trout that do not cohabit with brown trout.

Most of the other species hybridize with coexisting trout to a certain degree, or used to do so in the distant past, which is now evident in their genetic signatures. The softmouth trout from this river have a characteristically beautiful, golden sheen that has never been observed in any of the other softmouth trout populations. Unfortunately, at this moment there is no morphological data available to compare Vrljika and Neretva soft mouth trout.

The Zeta River (Montenegro)

The Zeta softmouth trout (Salmo obtusirostris zetensis) seems to be the most debatable of the soft mouth trout subspecies in terms of predicting its chances of long term survival. On the one hand, it is probably the most poached population of all five subspecies. Its very sad, but nets, harpoons, spear fishing, fish traps and excessive angling were all commonly used to remove them. Only the deepness and wideness of this river, its rich water vegetation, its karstic structure of underground wells and springs, and its densely overgrown river banks, have probably saved these fish from extermination.

On the other hand, recent studies undertaken by Mrdak et al. (2012), showed that the Zeta soft mouth trout has the highest genetic diversity of all the softmouth trout subspecies. If we consider that genetic diversity is required for populations to cope with environmental changes, and that the loss of genetic diversity reduces evolutionary potential and may, in the long term, cause species extinction, then there are no real concerns for the Zeta softmouth trout’s survival.

All that is needed is better river management. An immediate stop to poaching and a preservation of the quality of the environment. Hopefully valiant Montenegrins can do it. In the study I mentioned above, a detailed analysis of the softmouth’s feeding was undertaken for the first time. They feed mostly off benthic macroinvertebrates (fish predation is most uncommon). The gammarus shrimp is their most dominant food item (almost 90%). Now that certainly is a point to remember.

The Neretva River (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia)

The sharpest and the softest snout of all softmouth trout, along with a rather high growth capacity (up to 5 kg), appear to be the dominant characteristics of the Neretva soft mouth trout (Salmo obtusirostris oxyrhynchus) with a nickname Soxy, giving it a Coregonus (whitefish)–like look. Soxy has coexisted in the Neretva with native brown and marble trout for thousands of years. It was largely successful enough in avoiding inter-species hybridisation. Thus far has maintained its identity. This is probably due to different spawning times and possibly different spawning ground selection.

Nevertheless, soft mouth females are sometimes seen being chased by brown trout males during spawning. This may result in the sporadic production of natural hybrids observed in the Neretva. It seems, though, that the level of this natural hybridisation has not been high enough to break down the species barrier. The situation might drastically worsen if non-native brown trout are stocked. They tend to hybridise uncontrollably with all native trout. It creates a hybridisation bridge that can result in widespread panmixia and species break down.

Neretva River – Jewel in the Dinaric Alps

The Neretva is the largest karst river in the Dinaric Alps. The total length is 230 kilometres before it flows into the Adriatic Sea in Croatia. It rises from the base of the Zelengora and Lebršnik Mountains. It cuts its way down through countless rapids and waterfalls, carving steep gorges reaching up to 800 metres in depth.

The river is quite special within this group because it seems to be the only river where the soft mouth trout is increasing, at least in some parts. This is in spite of the fact that river management is far from ideal, and there is still a lot of poaching and over-fishing in some areas. The government has already built four dams on the river system, and they are building a fifth dam in the upper section. Still, I feel quite optimistic about the future of this river because there are some areas that are catch-and-release and fly fishing only.

Also, the Angling Club of Konjic does an amazing job, together with some local communities in the upper part. As a complete outsider, I see remarkable things happening in some parts of the Balkan, especially when local people start to join forces to care for their rivers. In all these areas, you see tourism booming as well. Many fly fishermen complain that rafting and canoeing cannot go together with fly-fishing, but as long I still catch fish between two canoes, I totally disagree with them. It works in perfect harmony in Slovenia, so why not in other countries, too.

Upper Neretva

The Upper Neretva has crystal clear water and is almost certainly one of the coldest rivers in the world. I drank the water several times while fishing the river and never had any problems. Even in high summer, the water temperature often stays as low as 7–8 degrees Celsius.

When local people care for their rivers, they find themselves not only accommodating fly fishers from all over the world, but many other tourists as well.