- A Historic Reintroduction Takes Shape - May 16, 2025

- Wrangler Duo Key to Wyoming Wilderness Adventure - October 1, 2024

- A Guide to the Best Flies for the Driftless Area - May 6, 2024

Michigan’s Artic Grayling could make a comeback.

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources has announced that the landmark stocking of Arctic grayling in select Michigan streams is scheduled for May 2025. The Arctic grayling reintroduction program commenced in 2017 and is being led by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR), in partnership with the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians (LRBOI).

The Arctic grayling is a historical species that was extirpated in the early 1900s due to overfishing in their native Michigan rivers and streams, introduction of competitive species, and northern woods logging practices which decimated their coldwater habitat. Extirpation means that the Arctic grayling were eliminated from the area, but not that the species itself became extinct.

The Arctic grayling is a coldwater species in the same family as salmon, trout and whitefish. The defining characteristic of this fish is its large, sail-like dorsal fin. While coloration can vary from stream to stream, their dorsal fins are typically fringed in red and dotted with large iridescent red, aqua or purple spots and markings. These colorful markings are most dramatic on large grayling. Arctic grayling backs are usually dark. Their sides can be black, silver, gold or blue. The iridescent hues of a spawning grayling’s dorsal fin are brilliant.

“Our formal mission as an initiative is to restore self-sustaining populations of Arctic grayling within its historic range in Michigan,” said Michigan DNR Fisheries Division Assistant Chief Ed Eisch. “Our program is not intended to be reliant on long-term stocking from our hatchery. Ideally, we will realize some recreational fishing at some point on select streams that can support grayling. We see this effort as a marathon rather than a sprint.”

Tribal Indian Organizations Are Key Partners

In 2010, the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians (LRBOI) began research to reintroduce Arctic grayling to northern Michigan. In 2016, to expand the workforce and research on Arctic grayling, the LRBOI and Michigan Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) entered into a partnership to restore Arctic grayling in northern lower Michigan.

“This is one of those fish that were here when the tribe’s ancestors were here,” says Archie Martell, LRBOI Fisheries Division Manager. “They were interacting with those fish, and it’s important to reconnect that interaction with the people and the fish and the environment.”

Today, Michigan’s Arctic Grayling Initiative consists of more than 40 organizations in addition to the DNR’s and LRBOI’s foundational partnership and is committed to re-introducing this culturally and historically significant species.

The program is being guided by a steering committee chaired by Michigan DNR Fisheries Chief Randy Claramunt, and includes representatives from each of the tribes involved in the partnership, Michigan Trout Unlimited as the non-government organization representative, and an at large member. The steering committee’s role includes deciding which streams will receive eggs and what type of follow-up monitoring will be implemented.

“Given the excitement around this effort, I expect the DNR and our other partners will be doing fish community sampling efforts, initially to assess survival of fry that hatch and emerge into the streams and, eventually, to assess whether natural reproduction is occurring,” said Eisch. “The real measure of success will be achieving self-sustaining populations of Arctic grayling that do not require stocked fish to supplement them.”

Streams Selected for 2015 Grayling Reintroduction

At the Michigan DNR May 2, 2024 Arctic Grayling Initiative update meeting, a finalist group of streams was announced for 2025 egg placement which includes the Upper Manistee River, Boardman River, and Maple River systems. All rivers are located in the northern section of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula.

Stream selection criteria included community support, historic range, and habitat potential (water temperature and diversity).

“We now have better conditions in our stream systems from a connectivity and water quality perspective for grayling success,” said Eisch. “Connectivity means fish can move from place to place which is important for grayling because they like to move long distances. And we feel our water quality is probably better than it’s been over the past 50 to 100 years.”

These river systems were selected based on water temperature, pool and riffle habitat, nursery vegetation habitat, and spawning substrate plus gradient flow. The vegetation habitat is important cover for grayling fry from predation by resident brook trout. The selected streams or stream sections feature brook trout which grayling have been able to co-exist with based on Nicole Watson’s research work versus brown trout which were seen as both competitors and predators of grayling.

“Brown trout are the bullies of the Michigan resident trout family,” said Eisch. “Grayling will move and by the time they wander into brown trout territory they should be of sufficient size to tolerate their competition for food and avoid predation.”

Key program partners responsible for egg introduction and monitoring are the tribal natural resource organizations assigned to each targeted river watershed:

— Upper Manistee River system: Little River Band of Ottawa Indians

— Boardman River system: Grand Traverse Bay Band

— West Branch of Maple River: Little Traverse Bay Band

Today, all of the tribes of Michigan have their own departments or employees devoted to conservation and natural resource management. Each tribe has a different organizational structure that may include conservation, fisheries, or wildlife departments, depending on the needs of their communities.

Initiative’s Four-phase Action Plan

Much of the initiative’s focus is detailed in its official Action Plan which was unveiled in July 2017 and is reflective of the vast work to be done by the various partners. The group gleaned as much information as possible from the state of Montana and their successful effort at re-establishing stable Arctic grayling populations.

“Within our Action Plan we identified four focus areas and associated goals that were developed by all the partners and that we believe will give us the best chance of success moving forward,” said Eisch.

The four focus areas of the Action Plan feature research; management; fish production; and outreach and education.

Research Led The Way to Stocking Plan

Nicole Watson’s work at Michigan State University focused on three areas: competition, predation and imprinting. Her work commenced in 2018 and was completed in 2021.

“What we wanted to figure out was what fish community grayling can survive and thrive in, and where they can have positive growth,” said Nicole Watson. “We looked into how grayling could compete with brook and brown trout which populate many Michigan streams as well as whether they could survive predation from them as fry.”

Watson’s research also looked into the importance of imprinting, which is the time when the grayling basically learn the smell or chemical fingerprint of the stream they were hatched in. A key learning from the research was the need to rethink the importance of imprinting in the early stages of a grayling’s development.

“We learned we could not stock 10-14-month old hatchery grayling directly into a stream because they would just wander,” said Watson. “Instead, we learned we need to use Remote Site Incubators (RSIs) which expose hatchery eggs in their new native stream water in a protective environment where they can grow into fry. The RSIs were the missing piece for a successful grayling reintroduction.”

RSIs have been successfully used to introduce fertilized Arctic grayling eggs into streams by Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks since 2003. RSIs are small, self-contained systems that allow the rearing and hatching of eggs directly at the site of introduction. Advantages of RSIs include allowing fish to hatch in the stream under local environmental conditions and facilitating early life-stage imprinting on the stream’s water. The use of RSIs to supplement natural reproduction and to reestablish fluvial Arctic grayling populations in Montana has proven more effective than traditional stocking practices.

According to Eisch, much more research is needed over the next five to 15 years as the initiative addresses river habitats, genetics, inter-species competition, RSI technology and function.

“There certainly will be additional years of stocking eggs into the three initial streams being targeted for the reintroduction effort,” said Eisch. “How many years will likely be determined by the steering committee and that decision will be informed by what is learned about the success of early efforts. Additional streams may be added, dependent on the number of eggs the hatchery brood fish produce and how things go with the first three streams.”

Management Phase Focus

A crucial step toward the reintroduction of Arctic grayling to Michigan waters began when 4,000 young, healthy fish were moved to a facility with conditions that triggered spawning. Michigan’s first year-class of future brood stock, averaging 6.5 inches long, was transferred in 2020 from the Oden State Fish Hatchery near Petoskey to the Marquette State Fish Hatchery where fish are reared in conditions that mimic the grayling’s natural habitat. The move was important because grayling need water temperatures and daylight that change with the season, and the water source at the Marquette hatchery does that.

The difference in the current program versus traditional stocking of hatchery fish was the decision to raise Michigan’s own grayling brood stock over three years to ensure quarantined rearing. Eggs were transferred from Alaska’s Chena River to Michigan’s Oden State Fish Hatchery in 2019 for the program’s first brood stock. After a year off in 2020 due to Covid, 2021 and 2022 year classes were raised with the 2022 year class transferred to the Marquette State Fish Hatchery in November 2023. Approximately 2,000-3,000 grayling were raised across the three-year classes for developing Michigan’s own strain of grayling and egg stocking via RSIs in selected streams in 2025.

“We are currently attempting to maintain between 1,500 to 2,000 fish from each brood year class,” said Aaron Switzer, DNR Fish Production Manager. “The current population is about 5,000 fish. We plan on creating new brood lots from subsets of the crosses between current brood lots.”

Switzer said the DNR is planning to have a ceremony at Oden State Fish Hatchery on May 12 to transfer eyed eggs over to the respective tribe that will be monitoring the egg introductions to each system.

Use of Floating Basket Incubators Key to Grayling Reintroduction

The fish production work features the successful use of Floating Basket Incubator designs (FBIs), ensuring fish health standards are upheld, and developing and maintaining a genetically diverse brood stock which will be housed at a state hatchery facility.

During 2022-2024, a team from Michigan DNR and Northern Michigan University tested a new instream incubator design against a traditional bucket-style Remote Site Incubator (RSI) design used by Montana’s Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks for their successful grayling reintroduction efforts. “We learned that many of our Michigan stream reaches lack the relatively high channel gradient needed to provide adequate hydraulic head for achieving target flow rates through an RSI for incubating grayling eggs,” said Troy Zorn, Michigan DNR Fisheries Research Biologist. “From conversations with Montana fishery managers, we learned that a traditional RSI may not be the only incubator design that might work for incubating grayling eggs to facilitate imprinting on the stream.”

“The comparative tests demonstrated that egg survival was comparable between FBIs and RSIs in lab and field settings. FBIs were much, much easier to deploy (in terms of equipment and staff needs); are simple by design; and operate reliably in low-gradient streams. We see them as preferable for grayling reintroductions in typical low-gradient Michigan streams,” said Zorn.

This discussion led to the exploration of various incubator design options for use in Michigan and eventual development of the Floating Basket Incubator (FBI) design that was built at the Marquette State Fish Hatchery and tested in hatchery and natural stream environments in the Marquette, Michigan area.

“The FBI is an entirely different type of incubator,” said Zorn. “The FBI is a flow-through design that is easy to deploy, and operates reliably in low-gradient reaches and low-velocity environments. The result was egg hatching success comparable to RSIs operating under best case scenario conditions. In the comparative tests, rainbow trout eggs were used because they are spring spawners like grayling and because Michigan grayling eggs were not yet available. We believe our experience with FBIs demonstrates that they will work as well as or better than RSIs in most low-gradient stream environments in Michigan for grayling reintroduction efforts. They are potentially useful for other species as well.”

Thousands of grayling eggs will be placed in FBIs in each participating stream by the program’s partners in May. For the Upper Manistee River watershed, the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians has decided to use both the floating basket and remote site incubators according to LRBOI Fisheries Division Manager Archie Martell.

Catch and Release Only Planned

“We expect the fish to be sexually mature at four or five years of age, but could be catchable by three,” said Eisch. “Our partners will certainly be surveying these streams to monitor how the effort is going. I expect annual surveys to start with our stream monitoring, but am unsure how long that will continue.”

Regulations have been changed so that it is no longer illegal to attempt to take Arctic grayling. That said, Arctic grayling are known to be subject to handling stress. The hope is that anglers will show restraint and not target them, even for catch and immediate release, until they become well established.

In November 2023 the DNR released surplus mature grayling—measuring 10-12 inches—into three Michigan lakes from its Marquette State fish hatchery. The DNR said that 400 Arctic grayling were stocked at West Johns Lake in Alger County; 300 were stocked at Penegor Lake in Houghton County; and 1,105 were stocked at Pine Lake in Manistee County. These grayling can be caught on a catch and release basis only as harvesting Arctic grayling is not yet permitted.

Michigan’s Grayling History

Michigan’s history with the Arctic grayling is long and storied. A striking fish with a sail-like dorsal fin and a slate blue color on its body, it was virtually the only native stream salmonid in the Lower Peninsula until the resident population died off nearly a century ago.

“The fact we have a town named Grayling after this fish indicates to me just how iconic it was and still is to many in this state,” Eisch said. “When you add in other factors—such as the fact they’re only native to Michigan and Montana out of all the lower 48 states—it just adds to their legendary status.”

Arctic Grayling in the Lower 48 States

While abundant in Alaska and British Columbia, Arctic grayling in the lower 48 states are a Pleistocene relic, left in northern Michigan and the upper Missouri River system by glacial meltwater. Most were river-dwelling (fluvial), but there was also a rare, lake-dwelling, river-spawning (adluvial) form. Ironically, adluvial grayling are easily transplanted outside their natural range, and after years of stocking, are now far more common in Montana’s high-mountain lakes than they were originally.

Fluvial grayling, on the other hand, are a very different species and can’t be replaced with the adfluvial form. Introduce grayling from a lake into a river and they’ll die out. Fluvial grayling require clean, free-flowing, medium-gradient streams with sand or gravel bottoms. Fluvial grayling were extirpated from Michigan over 90 years ago and they have been extirpated from 96 percent of their range in the West. Once abundant in the main stems and tributaries of Montana’s Smith, Madison, Gallatin and Jefferson rivers, they’re now barely making it in the upper Big Hole River. Factors contributing to their decline include dewatering by ranchers, habitat damage by cattle, introduction of non-native competitors and predators such as brown and rainbow trout, and dam construction.

Michigan 19th Century Extinction Causes

In the 19th century, northern Michigan streams were filled with fluvial Arctic grayling offering anglers plenty of opportunity to catch these unique fish. But a variety of factors slowly erased their presence, including the cutting of Michigan’s vast virgin forest in the 1800s.

“Logging practices during that time period used streams to transport trees that were harvested. The streams carried logs to mills for processing,” explained Eisch. “These practices greatly impacted the physical nature of those streams and basically destroyed stream habitats for fish, including grayling spawning areas.”

Additionally, the physical cutting of the trees caused blockages in many of those same streams, often displacing grayling from where they lived.

But this was just one issue that affected Michigan’s Arctic grayling. Another was the introduction of non-native fish species.

“Other species of trout were introduced into Michigan’s waters to create additional opportunities for anglers to pursue, but a consequence of this action was that grayling couldn’t compete with more aggressive fish like brown, rainbow or brook trout,” Eisch said.

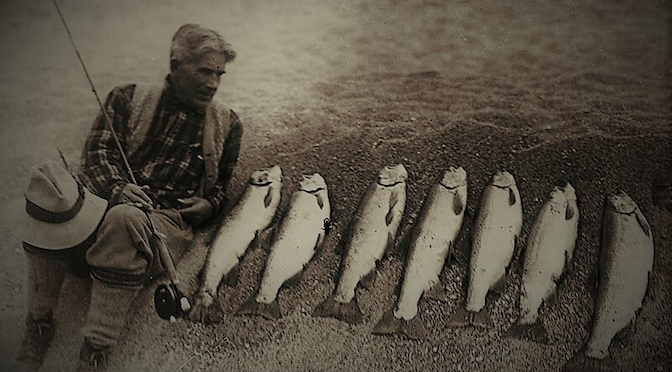

The final nail in the coffin was over fishing that occurred readily with people harvesting the grayling in large quantities with no possession limits or other regulations to stop them.

The last Arctic grayling on record in Michigan were taken in 1936, but since that time natural resource managers have repeatedly looked for options to reintroduce it.

Previous Re-introduction Attempts Fail

“In the late 1800s and early 1900s, millions of Arctic grayling fry were stocked into Michigan streams, but that didn’t work,” said Eisch. “And then in the 1980s, the DNR stocked hatchery-reared yearlings into lakes and streams, but again to no avail.”

In each of these previous re-introduction efforts something critical was missing that prevented these populations from flourishing, but the Michigan Arctic Grayling Initiative hopes to rectify that.

“We have learned from these previous re-introduction events and plan to capitalize on new approaches, dedicated partnerships, and advanced technology,” Eisch explained.

The key differences this time revolved around not stocking advanced stages of grayling; addressing critical imprinting periods; the use of strong genetic stock from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game; the development and use of floating basket incubators for eggs after learning from Montana’s remote site incubator experience.

Funding Is Another Priority

Funding was needed for each of the four focus areas, but primarily in the areas of research and fish production. The initiative has raised and spent approximately $500,000 to date. In the next 2-3 years, most of the funding will go towards stream habitat evaluations, fish rearing, equipment, and travel. According to Eisch, funding is not “complete” for any of the focus areas at this point in time and future funding will focus on private donations, Trout Unlimited national and local chapter support, foundations and company sponsors.

Almost Entirely Funded With Donations

Henry E. and Consuelo S. Wenger Foundation has been the initiative’s primary funding champion. The first grant came from Consumers Energy Foundation (CEF) followed by additional funds from the Wenger Foundation. Iron Fish Distillery in Thompsonville, Michigan, has contributed approximately $25,000 to date toward the program’s research. Michigan Trout Unlimited has also donated $25,000.

Individual donors can contribute directly to the State of Michigan with checks payable to Michigan Department of Natural Resources, Fisheries Division, and mailed to: Cashiers Office, Attn: MDNR Fisheries Division, PO Box 30451, Lansing, MI 48909-7951. The donations should indicate that the money is to be used for the Michigan Arctic Grayling Initiative.

Iron Fish Distillery, Michigan’s first working farm solely dedicated to the practice of distilling small-batch craft spirits, has introduced a commemorative rye whiskey celebrating its support of the reintroduction of Michigan Arctic grayling to its home waters. Iron Fish Distillery has made charitable contributions toward research into the viability of reestablishing native grayling stock to Michigan waters. Readers can go online and contribute to the Iron Fish Arctic Grayling Research Fund, a component fund of the Manistee County Community Foundation.

Iron Fish Distillery released its first Arctic grayling branded whiskeys in 2017 which helped raise awareness about the Michigan Arctic Grayling Initiative and encourage support by other groups and individuals. For seven years, Iron Fish Distillery has made charitable contributions to help fund the program’s research work in connection with Arctic grayling branded products. In 2019, Iron Fish introduced the first of three limited edition bottles of rye whiskey featuring an exclusive label of Arctic grayling artwork created by Michigan artist Dani Knoph. A fourth limited edition of 200 bottles was released in March 2025. This five-year-old commemorative whiskey is distilled from 95% rye grain grown on the Iron Fish Distillery farm in Thompsonville, Michigan and 5% northern Michigan 15 barley malted at Gray Lakes Malting Company in Traverse City.