- The Altitude of Ambition - February 10, 2026

- Can YETI’s new backpack deliver? Thoughts on the YETI CAYO - November 20, 2025

- How to Put a Worm on a Hook: Proven Methods for a Perfect Bait - November 18, 2025

I’ve always suspected that the best fishing stories aren’t really about the fish.

But about the geography of the soul. In early November, I traded the crisp orderly autumn of Munich for the Kenyan rainforest to test that theory with my friend Christian who flew half way around the world from New York to join the adventure. You don’t go to the African highlands for a high hook-up rate; you go for the glorious absurdity of pursuing a cold-water salmonid in the shadows of the equator.

If you tell someone you’re headed to Kenya, they envision red dust, acacia trees, and the heat-shimmer of the Maasai Mara. They don’t picture you in a fleece jacket, threading a 3-weight line through the guides while a cold mist clings to the moorlands. But that’s the secret: the British brought brown and rainbow trout here during the colonial era, and the fish didn’t just survive; they claimed the place.

The Aberdare National Park doesn’t offer a fishing trip in the traditional sense. It’s a game drive interrupted by moments of casting. Our guide, Tom Hartley, was the conductor of this orchestra. Tom has that uncanny, almost supernatural ability to “read” the bush—spotting a flick of an ear in the scrub or identifying a distant, guttural growl that would leave a city-dweller paralyzed.

The Symphony of the Mobile Camp

Home was a mobile camp Tom runs with his wife, Nikky. Calling it a “tent” feels like a betrayal of the experience. It was a sanctuary of unexpected luxury: a private loo, a hot shower, and meals that had no business being that good at high altitude.

But it’s the nights that stay with you. You lie there, zipped into the canvas, listening to the symphony of the wild—the sawing breath of a leopard or the distant, haunting whoop of a hyena.

The Deluge and the Detour

By day, we climbed into the rainforest, eating fantastic sandwiches on mossy banks while the clouds swirled around the peaks. At one point, we stood by a reservoir and watched a young bull elephant navigate the shore. On those reservoirs, when the breeze died and the surface became a mirror, the fish became ghosts; without a ripple to hide your intent, catching them was a fool’s errand.

The rain was our constant companion, turning the Aberdares into an elemental battlefield. Here, the “rivers” are really just high-altitude creeks, narrow and intimate, close to their birthplaces. To fish them, you have to be in proper shape; the bush is thick, the terrain is unforgiving, and every yard of progress is earned.

But then, a miracle: the rain would pause. The moment the clouds broke, the water would come alive with rising trout. Dry fly fishing proved not only the most exciting method but the most effective. These fish are wild and careful, but they are also perpetually hungry. Seeing a shadow break the surface of a mountain creek to take a dry fly is a specific kind of reward that makes the wet socks worth it.

On from the Aberdares

After a few days in Tom’s and Nikky’s marvelous mobile camp, we moved on to the Amboni Riverine Forest Camp, fishing the lower Honi. Here, the river is the passion project of Henry Henley, who maintains his beat with the meticulous care of an English chalkstream. It was a beautiful, surreal piece of Britain transplanted into the Kenyan wild.

Once we stopped fishing, the rain came back. The camp itself proved to be an adventure in the heavy downpour. Nestled deep into a gorge, the basic structures had difficulties coping with the elements and the only option was to pull the blanket up high to the chin and hope for less rain the morning after.

The Ragati Red

As the last and most adventurous stop of our trout safari we had hoped to reach Rutundu, the legendary cabins perched high on Mount Kenya. But the mountain had other plans. Inclement weather slammed the door shut, and we struggled even to claw our way out of the gorge at Amboni as the tracks turned to red slurry.

Tom decided to replace Rutundu with Ragati Conservancy, a Kenyan classic when it comes to trout fishing. The lodge is a rustic log cabin, stripped of the distractions of electricity. The only source of heat—and the heart of the home—is a constantly burning wood fire that fights off the damp chill of the rainforest. The local guides here are lovely, possessing a quiet wisdom of the water. They led us to the deepest pockets of the forest and cooked excellent, soul-warming meals for us every night and morning.

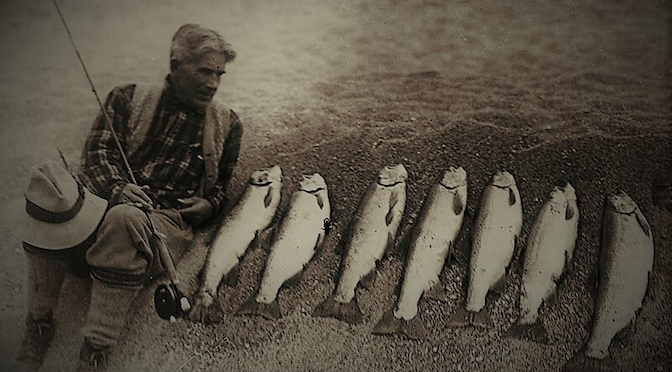

This is the home of the “Ragati Red,” a strain of rainbow trout so vibrant they look like they’ve been painted. The setting is a pure cathedral—deep, ancient rainforest on the southern slopes of Mount Kenya. We got one day of casting before the heavens opened again. The river rose, the water turned the color of chocolate, and the fishing was over.

You could call it a failure, I suppose. We missed Rutundu and got rained out at Ragati. But as I sat by that wood fire, I realized I didn’t care. I had seen elephants by the water and heard the mountain breathe. The “perfect” river doesn’t always need to give up its fish to leave its mark on you. We’ll be back. Not because it was easy, but because it was exactly the opposite.